These aren’t really “creator funds”

Campaigns like YouTube’s new Shorts Fund signal an encouraging shift in how tech companies do business. But it’s an incomplete solution for an inequitable creator economy.

Earlier this week, YouTube announced the Shorts Fund, a $100-million fund to be distributed through 2022. Shorts is the Google-owned social app’s answer to TikTok and includes a feed of brief videos posted inside the YouTube app. According to a blog post, YouTube will pay thousands of creators whose Shorts received the most engagement and views for their contributions. The recipients will be asked to share feedback so YouTube can improve the product experience. Anyone who creates original Shorts and adheres to YouTube’s Community Guidelines is eligible to participate in the fund, as it’s not limited to creators in the YouTube Partner Program.

The Fund is the latest in what feels like a flurry of tools and campaigns for creators to capture more of the economic value their work generates.

TikTok is reportedly working on new features for creators to share affiliate links with users in exchange for a commission and host QVC-like live-streamed shopping channels where folks can purchase goods with just a few taps.

In March, Spotify hosted a digital event designed to promote the company’s ambitions for mobilizing and empowering creators.

Weeks prior, Twitter announced Super Follows, a feature that allows users to charge followers for access to extra content like bonus tweets, invites to community groups, newsletter subscriptions or a badge indicating their support. (Just last week, Twitter unveiled Tip Jar, which its branded as new way for people to send and receive tips.

Last month, Pinterest launched a $500,000 fund for small groups of creators from under-represented backgrounds.

Then Clubhouse introduced Payments, its first monetization feature that enables users to pay money to a small test group of creators. (In January, the social audio app committed a portion of a new round of venture capital to a Creator Grant Program to support emerging creators.)

And a few weeks later, Facebook announced several new features coming to its flagship app and Instagram to enable creators to better support themselves through their work, including a tool that would allow creators to sell their products to their followers directly through their profiles on the app.

Just as one-time stimulus payments are good politics, these funds attract a lot of press coverage, most of it favorable or uncritical towards the companies that launch them. But as I wrote last month, these funds provide few paths to exploring management and representation for creators who are on the cusp of breakout fame but unsure of how to maximize it. What separates the upper echelon of creators from the unremarkable (or undiscovered) ones isn’t just money. It’s the infrastructure (or lack thereof) that’s required to earn a living off your creative work in the long term.

When news broke that YouTube was developing Shorts in April 2020, I wrote about the advantages the video app had with the short-form genre. The format is now familiar among most social app users, requiring little to no barriers to adoption for a product of YouTube’s size and reach. And it doesn’t hurt that the app has access to a massive music library thanks to its existing licensing agreements.

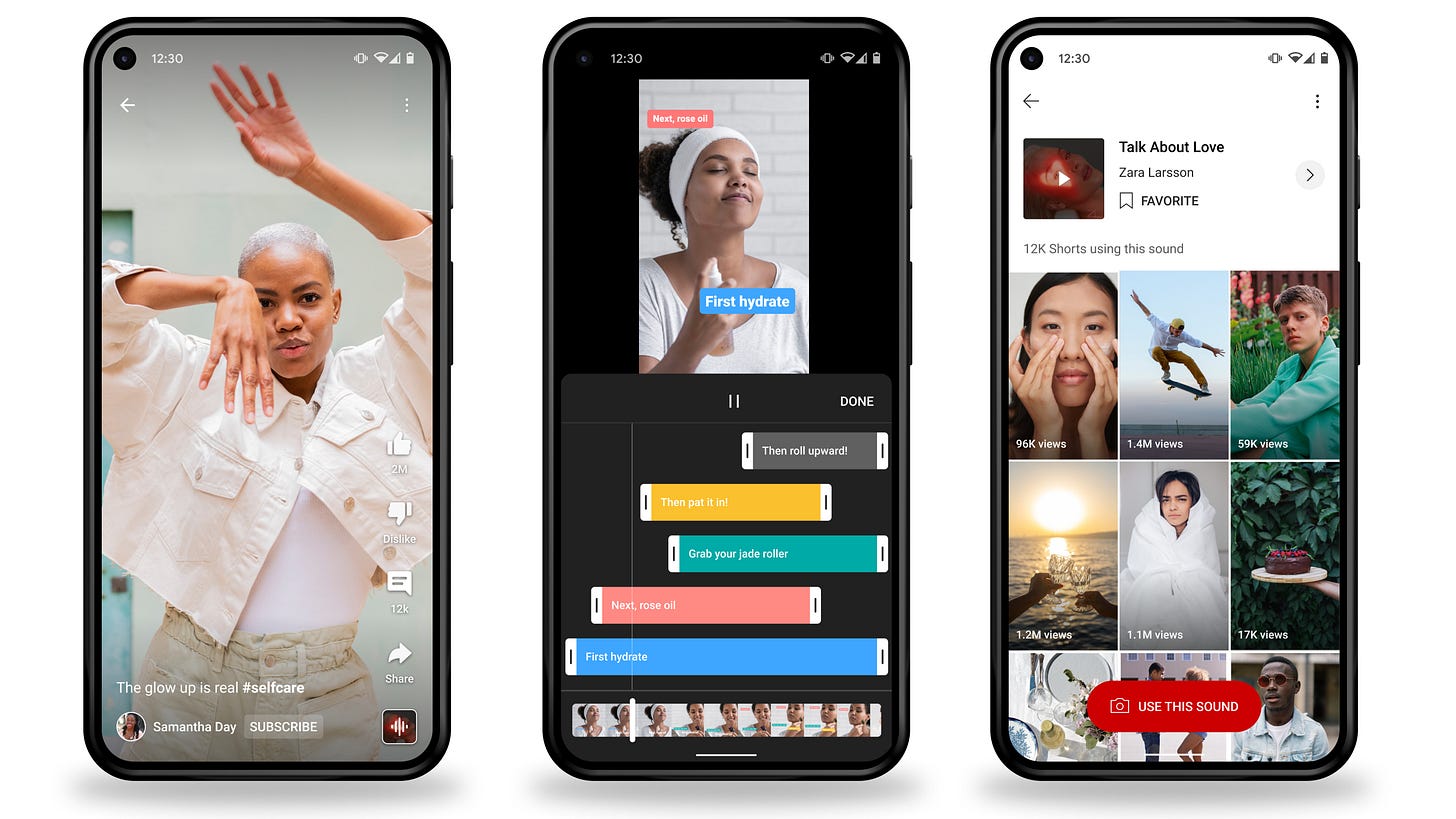

In the announcement for Fund, Amy Singer, director of global partnership enablement for YouTube Shorts, announced a suite of new features to make Shorts competitive with TikTok and Instagram’s Reels, including the ability to automatically add captions to your Short, record up to 60 seconds with the Shorts camera, add clips from your phone’s gallery to add your recordings made with the Shorts camera and add basic filters to color correct your Shorts — with more effects to come in the future. We’ll have to wait and see if any of them are sticky enough to pull creators away from TikTok to make a marked difference.

It’s also unignorable that the rise of the so-called creator economy is occurring alongside a larger labor movement against greedy corporate interests and anti-worker politicians. The narratives that people should be grateful to work jobs that pay poverty wages or accept “exposure” in exchange for creative work are finally being drowned out by a generation who refuses to return to the old way of doing life and business. And I’m grateful tech companies finally recognize that they’ll at least have to feign interest in the economic well-being of the creative class in order to maintain relevance going forward — this notion felt like an impossibility when I launched this newsletter 18 months ago. But engagement and views are terrible metrics to select funding recipients because they incentivize gimmicks, Blackfishing, and those who already have massive followings instead of skill, expertise and craft. Plus, the Shorts Fund fails to reconcile the issue of creative ownership. Sustainable creativity is only possible if creators own their work, the relationship with the fans and supporters it attracts and the value it generates. The Fund maintains YouTube’s role as a benevolent gatekeeper, but a gatekeeper nonetheless.

We could also stand to be more precise with our language. Because not of all them are “creator funds.” Some are just dollars earmarked for creative work with uneven terms set by the companies writing the checks. (It’s unclear if YouTubers helped develop the Shorts Fund; a company spokesperson didn’t respond to a request for comment by press time.) As long as one of the conditions for receiving funds is constraining your creativity to a specific app, then one-off payments will hardly ever be worth it for the reasons I mentioned earlier.

A true creator fund would enable recipients to accelerate and sustain their businesses, no strings attached. These companies can absorb the investment. If this seems radical or socialist or whatever the GOP buzzword of the week is, it’s only because we’ve accepted the idea that tech companies shouldn’t have to pay for creative work because their tools enable it and American capitalism is based on a meritocracy. However, I’ll always live on the side of giving creators maximum freedom to choose the tools on which they make, brand, market and sell their work — and to spend the money it earns however they want.

But who am I to encourage creators to turn down a cash lump sum? I make my money from reader subscriptions. So of course I’m disinclined to trust the motives of powerful tech giants. You’re welcome to question mine whenever I critique ecosystems that I feel are antithetical to collective interests. Plus, I’m clear that not everyone in the creative class is as skeptical as me or other like-minded critics. And honestly, that’s what companies like Google are counting on. If recipients of these “rewards” are unbothered by or unaware of the downsides of these funds, then $100 million — which, for perspective, less than two percent of YouTube’s ad revenue from the last quarter alone — will turn out to be money well spent.

Coming tomorrow: “Do you feel imposter syndrome?”

In tomorrow’s subscriber-only issue of Ask Michael, I share my thoughts on imposter syndrome and the extent to which it affects my creative work as a journalist.

Ask Michael is a weekly column in which I answer reader-submitted questions on current events and how to make, brand, market and sell creative work with confidence and clarity. My answers are rooted in personal experience and observations. And since I’m a reporter by trade, so I know how to find experts to share their knowledge if your question is outside of his zone of genius.

In addition to Ask Michael, paid subscribers also get access to my private calendar for virtual office hours, commenting privileges and 24/7 access to the full archive.

Subscribe to The Supercreator to get Ask Michael sent straight to your inbox tomorrow morning.

Read All About It

Jacob Silverman at The New Republic on the “labor shortage”:

The supposed labor shortage—one generated by an allegedly too-generous welfare system—is anything but. Among the economic lessons of the pandemic is an obvious one: Wages are too low, jobs too shitty. If employers want workers to return to flipping burgers for possibly unvaccinated customers in the midst of the greatest public health crisis in America’s history, then they should pay them more. If the government is beating the private sector in terms of providing a livable wage, that is a fault of business owners, who, in their infinite self-regard, seem to think that workers should be grateful for whatever crummy, sub-subsistence job they manage to get. (It’s also an argument for the government to get in the business of enforcing livable wages.)

Ken Budd at The Washington Post on affection between straight men:

For many men, that contempt begins as boys. In a study published in the journal Child Development, middle school boys said that talking about their problems is weird, uncomfortable and a waste of time. Meanwhile, an Irish study found that emotionally distressed young men “desperately wanted closer social connections and support from family members and friends,” but “feared being judged as emotionally vulnerable, weak and un-masculine.” Our emotional suppression could even be killing us. When you don’t talk about your feelings, your risk of death from any cause increases by 35 percent, and from cancer by 70 percent, according to a study in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research.

Estelle Kang at BuzzFeed News on therapy and people of color:

This means it’s common for people of color to end up working with a white therapist who doesn’t understand the complexities of their identity and experiences. Alison Chou, who is pursuing a master’s degree in social work at Columbia University, had one such encounter. “She was an older woman from the UK,” Chou told me over a video call. “I'm a bilingual Spanish speaker, and she kept getting really hung up on that. She was like, ‘How do people react to you when you speak Spanish? Because you don't look American’ — she just blurted that out. She started to correct herself, and I was just like, ‘Because I don't look white American?’” Chou stopped working with that practitioner. “That really killed it for me because I learned two things about her worldview: She couldn't perceive a world where an Asian woman could speak Spanish. And, clearly, even if she didn't think it consciously, she was thinking, This person doesn't look American.”

Terry Nguyen at Vox the buy-now, pay later for health care:

These buy now, pay later providers have spent years slowly infiltrating the retail market through partnerships with merchants, but the pandemic has accelerated their popularity among online retailers, from luxury brands to independent shops to fast-fashion sites. As a result, more consumers have grown familiar with these services, many of which have buzzy two-syllable names like Affirm, Klarna, Quadpay, and Sezzle.

These startups sell the myth that shoppers are in greater control of their money, even while they’re fulfilling their consumerist desires. Customers, particularly those who are budget-conscious or financially constrained, are under the illusion that they’ve spent less and are able to hold on to their hard-earned cash for a few weeks longer. Meanwhile, for retailers, a service like Afterpay could theoretically increase the average value of a shopper’s order — encouraging them to spend money they don’t presently have.

It doesn’t end with retail, though. Emerging fintech apps are looking to apply this lending model to other sectors, from health care to travel to rent. Sure, people are growing acclimated to dividing their purchases into four easy payments, even applauding the option to do so. But no matter how you frame it, the pitfalls of these plans seem to be, unfortunately, just more debt.

Will Oremus on The Atlantic on Clubhouse’s black badge:

When you block someone on Clubhouse, it doesn’t just affect communications between the two of you, as it would on Facebook or Twitter. Rather, it limits the way that person can communicate with others too. Once blocked, they can’t join or even see any room that you create, or in which you are speaking—which effectively blocks them for everyone else in that room. If you’re brought “onstage” from the audience to speak, anyone else in the audience whom you have blocked will be kept off the stage for as long as you’re up there. And if you’re a moderator of a room, you can block a speaker and boot them from the conversation in real time—even if they’re mid-sentence.

Imagine a live panel discussion in which each member of the panel has the power to cut the mic of any other member, at any moment and for any reason, and also the power to have that person dragged from the lecture hall by security. That’s roughly how blocking works on Clubhouse. This is not just a personal decision, but a social act, with implications for who can speak at what times and in what settings.

There’s even a visible emblem of this regime. When a user you don’t follow has been blocked by some unspecified number of people whom you do, that user’s profile will appear on your app with an ominous icon: a black shield with a white exclamation point. Clubhouse calls this feature a “shared block list.” Some users call the badge the “black check mark” (or even the “black mark of the damned”), as if it were an inversion of Twitter’s blue check mark, signaling notoriety instead of notability. While others can see it on a user’s profile, the user herself cannot—and most don’t even realize they’ve been marked until someone else breaks the news.

Sophie Kemp at GQ on Twitter’s new font:

Spend any time on the New York City subway system, and alongside telephone numbers for Coney Island-based psychics and personal injury lawyers, you’ll see ads for Glossier, bespoke Viagra subscriptions that feature cacti in their marketing, and dating apps ads designed by Italian artworld lotharios Maurizo Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari (Hi, OkCupid!). The typefaces on all of these advertisements are meant to seem approachable, easy on the eyes. Even if you have no intention in ever purchasing Brooklinen sheets, you’ve probably seen the soft, swooping lower case ‘B,” out and about, and maybe Googled them, just to see if maybe they actually are all that great. These styles of type feel akin to the labels on cans of craft beer, gig posters, and the covers of hip essay collections. With its new custom typeface, Twitter is joining these ranks: Chirp fits right in. It will be interesting to see the effect that the Chirp has on users over the next few months. Will people really bare it all in a whole new way?